Why 2024 Might not be the Year for Generative AI in Banking

GenAI uptake a slow burner for banking industry

The release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT model in 2023 marked the arrival of a new technology: generative artificial intelligence. (GenAI) is the process whereby a machine scours the internet to create unique text – or other outputs – in answer to a query or instruction. From education to e-commerce, this emerging technology is infiltrating several industries at breakneck speed.

However, one industry where the integration of GenAI may be lagging is banking.

2023 was a difficult year for the banking industry. Rising inflation, declining bank fees and systemic shocks such as the Silicon Valley Bank collapse put a squeeze on cost margins, while also bringing caution and a risk-averse sentiment.

It appears this sentiment has carried over into 2024, with potentially negative implications for the uptake of generative AI technologies in the banking industry.

Current data from Cornerstone shows that banks may be putting GenAI implementation on the back burner and are instead prioritising cost savings rather than technology spending as we head further into 2024.

A survey of 359 respondents from global financial institutions in the $250 million to $50 billion asset range, found that 70% of banking executives said costs of funds (the amount of money a bank pays in order to obtain funds for reserves and lending) as their top concern in 2024. This is almost a ten-fold increase from the 8% figure recorded in 2021, underscoring the significant macroeconomic headwinds currently facing the banking industry and the resulting shift in priorities.

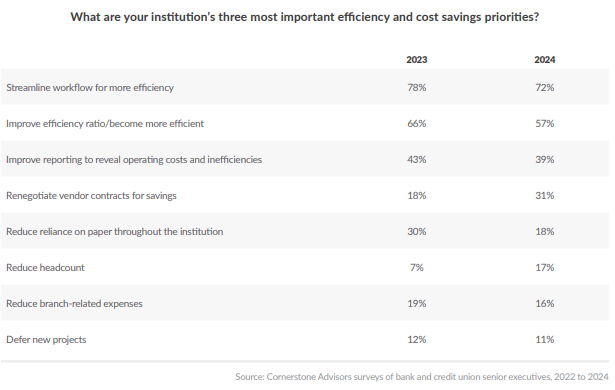

What is also striking is the banking industry’s priorities in terms of efficiency and cost savings.

As you can see, reducing headcounts has become a larger priority for banks in 2024 compared to 2023. 2023 was a record year for job cuts among the world’s 20 largest banks, with more than 60,000 layoffs announced, with more of the same expected in 2024. This could invariably leave banks with less skilled staff to operate and oversee GenAI, meaning that uptake of the technology may be sticky. The table shows there is also a marked decrease in banks’ desires to reduce reliance on paper and manual processes. This in itself indicates that banks’ uptake of GenAI may be sluggish, as GenAI is built around automating tasks and reducing reliance on manual operations. For example, one use case of generative AI in banking is to extract insights from reports, market data and news releases.

Just 6% of banking institutions have deployed or are invested in GenAI, which is substantially lower than other subsets of more established AI techniques, such as machine learning (16%) and chatbots (20%). Only a handful of large banking institutions have taken the plunge into generative AI. For example, last year, JPMorgan filed for the trademark of IndexGPT, a ChatGPT-like software service designed to provide personalized investment advice to customers. In addition, Morgan Stanley Wealth Management has announced that it will use OpenAI’s GPT-4 to deliver content and insights into the hands of financial advisors.

Aside from macroeconomic headwinds, there are other factors contributing to banks’ apparent reluctance to adopt GenAI models. One such example is the prevalence of data bias, where poor quality data inputs can lead to generative AI models spewing out inaccurate and faulty outputs. This can contribute to a lack of trust and uncertainty toward generative AI technologies. (Learn more about this in our ‘Powering the Trade Lifecycle with Generative AI’ report here.)

Of course, it is still early days for GenAI, so immediate widespread adoption of in the banking industry would be wishful thinking given the nascency of the technology. However, for all the furore and excitement surrounding it, globally, it seems that the banking industry doesn’t currently accept this view, with cost-cutting currently the main objective for many banking institutions. Uptake of GenAI may therefore be slower than expected.

The GreySpark article offers a thoughtful perspective on the cautious adoption of generative AI in fintech for 2024. While the potential of generative AI is immense, it's essential to balance innovation with practical considerations.

Generative AI is already making significant strides in areas like personalized financial advice, fraud detection, and compliance automation. For instance, banks and financial institutions are leveraging AI to enhance customer experiences and streamline operations.

However, as highlighted in the article, challenges such as data privacy concerns, regulatory compliance, and the need for robust governance frameworks are critical factors that institutions must address. It's not just about adopting new technology but ensuring it's implemented responsibly and ethically.

For those interested in exploring the transformative impact of generative AI in fintech further, this article provides valuable insights: [https://www.cleveroad.com/blog/generative-ai-in-fintech/