It’s a case of when, and not if, Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) become a base layer of global payment systems.

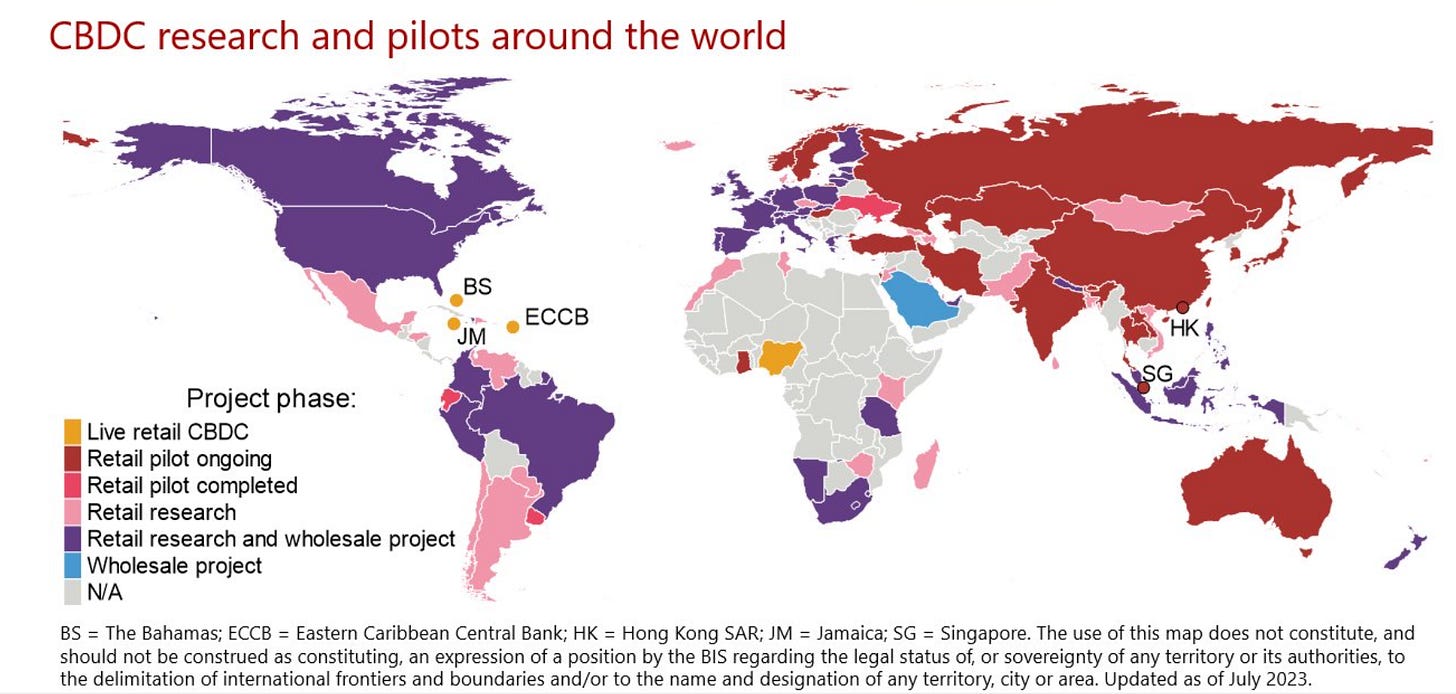

According to Reuters, 130 countries, representing 98 percent of global GDP, are “exploring” CBDCs in some way. Additionally, according to the Bank of International Settlements, roughly 93% of banks are exploring CBDCs.

In fact, four countries, including Jamaica and Nigeria, have launched their own retail CBDCs. India and Brazil are planning to launch their own CBDCs next year, with India’s current CBDC pilot being tested by 1.5 million users.

But what are CBDCs, and more importantly, how will they work?

Currently, the public can hold money issued by the Central Bank in the form of banknotes, but only banks and certain other financial institutions can hold electronic central bank money, which comes in the form of reserves. A CBDC would be an electronic form of Central Bank money that could be used by households and businesses to make payments and store value. CBDCs will co-exist with cash and bank deposits, rather than replace them.

To be clear, although the majority of currency that exists today comes in digital form, and that CBDCs fit the definition of being a “digital currency,” CBDCs are different from traditional fiat currencies.

As CBDC/blockchain specialist Mustafa Syed explains:

Traditional money is created through commercial banks through the fractional reserve banking systems, and the assets and liabilities are held on the balance sheets of such banks and client. In contrast, with CBDCs, the liability would be held at the central bank and they would be responsible for issuing the digital token. The central bank would need to maintain the reserves to back the liability.

Generally, there are two types of CBDC — wholesale and retail CBDCs.

Retail CBDCs have wider use, being issued for the general public and tailored to facilitate smaller transactions between people and businesses. On the other hand, wholesale CBDCs are optimised for financial institutions who hold reserve deposits with a central bank, and are used to facilitate large cross-border settlement asset in the interbank market.

Given that CBDCs are still widely under development, the narrative about them largely comes from a hypothetical standpoint.

Nevertheless, CBDCs require the development of new technological infrastructure and payment rails to accommodate them.

From a retail standpoint, this infrastructure includes everything from the database on which a CBDC is recorded, through to the applications and point‑of‑sale devices that are used to facilitate payments. CBDCs would offer users another way to pay, which may ultimately be faster and more efficient than current systems.

The centre of the CBDC payment system would be a core ledger that records the value of CBDC value itself, and processes every transaction made using that particular CBDC.

In the use of ledger technology, CBDCs draw some parallels to the cryptocurrency market.

The use of ledger technology underpins many crypto networks, which acts as a repository for the recording of transactions.

CBDCs also emulate cryptocurrencies in the sense that they could boost transparency, payment efficiency, security and financial inclusivity. For instance, like with crypto blockchain-based transactions, each CBDC user will have a unique digital identity traceable on a ledger system. Additionally, according to IBM, around 1.7 billion people currently don’t have access to basic financial services. CBDCs can provide digital currency to anyone with a smartphone, without the need for a bank account.

However, it’s key to remember that fundamentally, CBDCs and cryptocurrencies are not the same.

CBDCs are issued by centralised authorities and are recognised as fiat currency. In contrast, cryptocurrencies are de-centralised and provided by private markets.

This table from Cato Institute shows the main disparities between CBDCs and cryptocurrencies.

Aside from a ledger, there are two other critical layers in the use of CBDC systems — Payment Interface Providers (PIPs) and Application Programme Interfaces (API).

PIPs refer to private sector firms that manage all the interaction with users of CBDC and provide overlay services that extend the functionality of CBDC. APIs provide the connectivity to the core ledger.

PIPs and APIs include providing mobile applications or websites to allow the user to make CBDC payments, providing know your customer (KYC) checks and ultimately, maintaining individual accounts in the core ledger for every user.

Below is the hypothetical platform model for retail CBDC operability. It shows the framework for which private sector firms could connect to the ledger in order to provide customer-facing CBDC payment services.

The above model can also be recognised as one of three retail CBDC architectural models — the indirect CBDC model. The other two are known as the direct model and hybrid models.

Simply put, the indirect model will see intermediaries (i.e commercial banks) provide services to manage payments from businesses and individuals. The direct model eliminates the need for intermediaries, with consumers and businesses holding direct accounts with the Central Bank. The hybrid model is a combination of both, with payment providers managing know your client (KYC) and retail payments and the Central Bank managing the balances for the end users.

The chart below shows each model in greater detail:

In truth, there are several iterations of what CBDC architectures could look like. It’s likely that Central Banks, commercial banks and policy makers will have to refine their design choices, and stay on top of the latest system developments.

Ultimately, the implementation of CBDCs present structural challenges, and currently, there isn’t really a “one size fits all” solution that will enable instant interoperability between CBDCs systems across different jurisdictions. This also poses regulatory uncertainties, with an international framework likely needed in the long run if CBDCs are to thrive.

With CBDCs seeming an inevitability, going forward, it’s imperative that stakeholders (i.e. retail banks, merchants and Central Banks) start preparing for their arrival. According to McKinsey and Company, they may do this by:

Optimising their infrastructural design choices for CBDC functioning and interoperability;

Giving consideration to the level of infrastructure investment needed and;

Developing KYC and anti-money laundering systems which can accommodate CBDCs.

Nevertheless, the transition toward CBDCs and the technology underpinning it is something we will be keeping a close eye on here at GreySpark. Ultimately, it could go on to form a key part of banks’ technology stacks for years to come.