After the Markets-in-Crypto-Assets (MiCA) regulation, the European Union has once again become a first mover in drafting specific regulations for nascent technologies that are primed to revolutionise the capital markets landscape.

In December 2023, the EU reached a provisional agreement on the new EU Artificial Intelligence (AI) Act. Although the legislation has not officially been implemented, it marks the arrival of the first comprehensive set of AI-specific regulations that the world has yet seen. It is expected that the text will be formally adopted by both the European Parliament and Council to become EU law, which will likely happen in early 2024, before officially entering into effect in 2026 following a two-year transition period.

Recent developments in the adoption of the AI Act have arguably come at a good time. The furore, uncertainty and interest toward AI currently remains at an all time-high, with the rapid proliferation of specialist AI models, such as Open AI’s ChatGPT over the past year. Nevertheless, question marks still remain about the long term viability of AI, in terms of its accuracy, its ability to replace humans and its safety. As such, a specialised AI regulatory framework should go a long way in harnessing its undeniable power, but also providing an adequate level of protection for users.

What is the EU AI Act?

As stated, the EU AI Act is a legal framework governing the use of AI in the EU.

The definition of “AI system” is aligned with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) definition of AI system. An AI system is now defined as:

“A machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that can, for explicit or implicit objectives, generate outputs such as predictions, recommendations, or decisions that influence physical or virtual environments.”

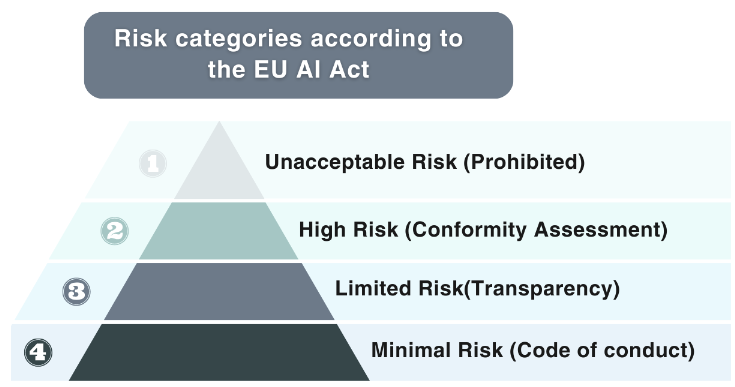

As the image below shows, the EU AI Act has classified AI systems into four risk categories, with each calling for differing levels of regulation.

Unacceptable Risk - AI systems belonging to this category are prohibited entirely. Unacceptable risk systems are defined as those that have significant potential for manipulation, or can exploit vulnerabilities. An example includes the use of real-time remote biometric identification in public spaces. These systems are generally out of scope for the financial services industry.

High-Risk - High-risk AI systems must meet various requirements. These include; risk management, data governance, monitoring and record-keeping practices, human oversight obligations, and standards for accuracy, robustness and cybersecurity. High-risk AI systems must also be registered in an EU-wide public database. Credit scoring of banking customers can fall into this category.

Limited Risk - Includes chatbot systems. These AI systems should comply with minimal transparency and disclosure requirements, ensuring users are aware that they are interacting with AI systems.

Minimal Risk - Includes applications that are already widely available, such as spam filters that will be largely unregulated.

General purpose AI models (such as generative AI models like ChatGPT) are treated separately from these risk categorisations. In particular, providers will need to make information available to downstream users who intend to integrate the GPAI model into their AI systems, assess and mitigate systemic risks, and conduct adversarial training of the model. More details can be found here.

Why is the EU AI Act being implemented?

The European Commission cited various factors in its decision to propose the Act, including the growing importance of AI in the global economy, emerging use cases in sensitive areas such as healthcare and law enforcement, and the need to ensure that AI is developed and used in a way that is safe, ethical and accountable. There are also economic motivations – the EU is seeking to take a leading role in setting core standards around AI trustworthiness and ethics, in the belief that it will obtain a larger share of the global AI economy.

Who could be impacted by the EU AI Act?

If implemented, the EU AI Act will apply to all EU companies that use AI-based systems, based on the definition above. That includes providers, manufacturers, importers, distributors, and deployers of AI from all industries, which of course includes financial firms. AI developed for military and scientific purposes are excluded from the legislation.

Although this is EU legislation, the AI Act will have a degree of extraterritorial effect, such as where companies outside the EU sell their AI systems to businesses in the EU or make their AI systems available to users in the EU. For example, if a company in the US develops a platform which uses AI to make decisions about applications for financial products made by EU consumers, such as credit scoring apps, which will be categorised as high-risk, the Act will apply even if that US company does not have a presence within the EU. The EU AI Act will not apply to high-risk AI systems that are placed on the market or put into service before the date of application of the AI Act (two years after it becomes law).

Broadly speaking, EU banks and investment firms are already subject to extensive prudential requirements on corporate governance, systems and controls, risk management, operational resilience, outsourcing and cyber-security, as well as requirements on product governance, conflicts of interest and the protection of customer interests. The current use of AI comes under these requirements, without being explicitly covered by regulatory frameworks such as MiFID II and the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA). For example, the technical standard RTS 6 in MiFID II regulates algorithmic trading among financial firms, which is of course AI-centric. DORA will cover all third-party ICT risks, including AI solution providers, from the January 2025 implementation date.

Generally speaking, though, AI is only covered implicitly in patchwork among regulatory bodies. Given the latest advances in AI, such as the proliferation in more sophisticated AI tools, the current regulation for AI is inadequate, and hence calls for AI-specific regulation such as the AI Act.

However, as of now, the regulations are currently early stage, with the only explicit references to financial services use-cases in the initial drafting being credit-scoring models and risk assessment tools in financial institutions. We expect the requirements to become more wider reaching once it is officially announced into EU law. Nevertheless, there are still some general implications that the AI Act will have for financial institutions that are worth considering. The AI Act mandates transparent, interpretable AI models and the use of unbiased, high-quality data. High-risk applications, like credit scoring models, will require mandatory impact assessments. Other implications of the Act include:

Risk Management: Thorough assessment of AI systems for compliance with the Act’s risk categorisation, as shown above.

Enhanced Transparency and Accountability: Clear communication of AI tools used in customer interactions.

Data Governance: Requirement for unbiased, high-quality data in AI models.

Regulatory Compliance: Alignment of AI deployments with the Act’s directives.

While the EU AI Act has not officially been entered into law, it is looking increasingly likely that it will be, with the final text currently being drafted. With this in mind, giving some consideration to the future implications of the EU AI Act could help give firms a head start in applying robust, compliant AI-based operating models.