ESG is arguably one of the most important investment trends of the decade. The acronym stands for: environmental; social; and governance. Broadly speaking, you could encapsulate these terms under the term ‘sustainability’ with corporations, financial institutions and governments being assessed against their ability to ‘do good’ and implement more ethical practices. Examples of ESG practices include energy consumption, encouraging workforce equality through pay and diversity, and business transparency; for instance, in reporting financial performance and business strategy to stakeholders.

Recently, ESG has taken on a greater importance across several industries. One could argue that the most prominent aspect of the ESG trend is the environmental aspect. As the world grapples with the growing issue of climate change, a sense of urgency in meeting net-zero climate targets has ensued, fuelled by tougher and more nuanced regulatory standards, which you’ll see more on below.

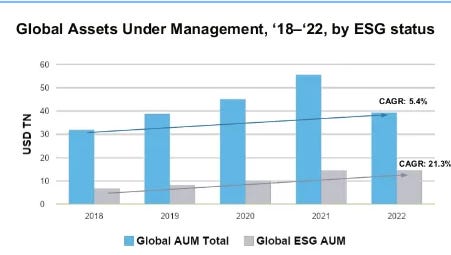

The hard numbers reflect the growing ESG trend. In the past five years, ESG-labelled assets under management (AUM) has more than doubled. Most impressively, as shown below, ESG AUM resisted the effects of 2022’s interest rate rises to register a small increase in AUM, against the backdrop of a more-than 10% and $10 trillion fall seen in the global AUM figure. This a trend expected to continue, with just 7% of asset managers and less-than 2% of asset owners not planning to integrate ESG into their investment processes.

Source: GreySpark analysis

However, those who haven’t yet implemented ESG regulatory practices may be doing so at their peril. The ESG regulatory landscape is evolving at a significant pace, with different regions introducing their own iterations of ESG regulations. The three major geographies of global Capital Markets (EMEA, Americas, APAC) have their own distinct approaches to ESG:

ESG is most firmly established in EMEA. All forms of sustainable investment have been adopted here more than in other regions. Investor demand for ESG is higher in EMEA than elsewhere, but the biggest driver is financial regulation. By 2025, the EU’s ESG regulatory framework will be fully established and active.

US sustainable investment is driven by fiscal policy, asset managers and individual investors. BlackRock and others have been impactful in terms of shareholder activism and thought leadership. Regulation has played less of a role,

mainly targeting specific issues, i.e. disclosure of board diversity and pay.

APAC countries have had a varied approach to ESG. The most developed markets (e.g. JPN, AUS) have seen swelling interest in ESG from individual investors, matched by asset managers. In the less developed markets (e.g. CN, SEA, IND) regulators have focused on green finance, but less so on ESG.

The EU arguably has the most comprehensive set of capital markets ESG reforms in the three aforementioned regions, with the UK seeking to follow its lead. Under the terms of the European Green Deal legislative package, the EU is seeking to cut its net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, compared to 1990 levels.

As Envoria highlights, as part of the European Green Deal, the EU has outlined the Sustainable Finance Framework, which is intended to help embed sustainability factors at various levels of the economy. The Sustainable Finance Framework includes the application of new EU regulations on corporate transparency. The three most important are the EU Taxonomy, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). SFDR is specific only to investment firms, whereas the EU Taxonomy and CSRD also applies to non-financial companies.

The EU Taxonomy Regulation is a classification system that sets criteria to determine if an economic activity by a firm can be considered sustainable. One of the main criterion is whether the firm involved is making a substantial contribution to at least ‘one environmental objective.’ You can see the six objectives below.

Taxonomy Reporting against the six environmental objectives is typically expressed as a ratio, for example: ‘What proportion of the firm’s turnover substantially contributes to climate change mitigation?’. This question would likely be answered through a percentage-based assessment. Currently, firms are only expected to be compliant with climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation.

In addition, CSRD requires larger corporates (typically those with an annual turnover above €150 million) to include ESG reporting within their management reports or separate non-financial statements. CSRD has brought 50,000 corporates into scope for reporting, and must report on metrics such as greenhouse gas emissions, employee safety and diversity, and anti-corruption.

Finally, SFDR obliges financial firms to disclose information about how they factor sustainability into their business processes (data providers, strategy etc), as well as about their own ESG performance (renumerations, emissions produced).

The current European ESG regulatory landscape can perhaps be better seen with a timeline.

Source: GreySpark analysis

This year marked the start of SFDR reporting, whereby mandatory reporting templates were introduced, along with more nuanced SFDR regulations - for instance, investment firms now have to disclose what proportion of its assets are invested in areas subject to ‘principal adverse impact’, which provides transparency on investment decisions. The UK’s FCA is expected to endorse its equivalent ‘sustainability and disclosure requirements’ by July 2024.

Next year, investment firms in scope of the EU regulations are expected to become compliant with all six EU Taxonomy objectives highlighted above. 2025 is expected to see the introduction of the first regulations for ESG data and software providers. Finally, in 2026, small and medium-sized enterprises will join larger corporates in reporting under the terms of CSRD.

ESG regulations are continuing to evolve at a rapid pace, with the world vying to meet sustainability targets, particularly in the face of growing climate change pressures. From a financial and reputational standpoint, it is imperative that financial firms start taking their ESG practices seriously, if they are to stay relevant to the world of today.